I’ve given this sermon the name "Selfishly Waiting for a Miracle." The "selfish" part will be explained in due course; Advent is a time of waiting; and today’s Gospel reading reminds us how important the idea – the fact – of miracles was to the followers of Jesus. In Matthew 11, we learn about the signs that Jesus points to, in answer to John’s question, "Are you the one?" Most of them are miraculous, including this one: "The dead are raised."

|

|

|

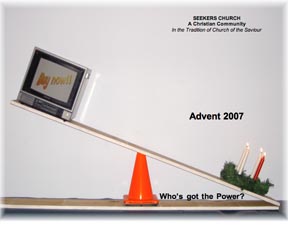

Altar installation showed the advent wreath |

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus turns back death, culminating in his own resurrection. The Gospel accounts are straightforward. We are free to read them as straightforward metaphors, of course, or exaggerations, or pious accretions to the story of Jesus’ life, added by Mark and Matthew and Luke and John long after the fact. For many Christians – for many here, I’m sure – a single, non-miraculous sign is all we need: the Good News is preached to the poor. Isn’t this miracle enough, really? That the message of God’s love and mercy was preached loud and clear, and thanks to the example of Jesus’ life, we have a teacher and brother we can follow confidently as we grow in the likeness of God?

Actually, no, that isn’t enough for me. I want the signs and wonders too. I want the miracles. And especially I want the central Christian miracle, the amazing story of how the Son of God defeated death itself, and offers this same gift to each one of us. Paul said, "[I]f the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins." I don’t feel the need to go that far, but I will say that, without the hope of resurrection, my Christian faith feels muted, impoverished. As we sang this morning, I want "death’s own shadows put to flight."

I’ve led a very fortunate life. In a world brimming with hardship and oppression, I found myself born into comfort. No one has oppressed me, and for that matter, no one has forced me to take up arms in the oppression of others. God has given me gifts and talents. At nearly every turn, when I’ve looked for God’s love, I’ve found it. Whatever rough spots I’ve had to endure in 53 years, they don’t strike me as much different from the challenges most of my peers here in middle-class America have faced.

There is one exception to this blessed life. In 1995, my lifelong and dearest friend died of a heart attack at the age of 42. There was no warning, no premonitory illness. He simply dropped dead one morning. His name was John Talbert. He left behind his wife Kathy, his five-year-old daughter Jacqueline, and his three-month-old daughter Madeleine, who is my goddaughter.

Nothing prepared me for the loss of this man. I’m an only child, and John was the brother I never had. We would call each other up just to yack, for no reason, as siblings do. We saw each other several times a week, because John was a fellow musician and also a fine writer, and we spent hours in each other’s company, sharing the things we loved. He was the funniest guy I’ve ever known. And as it happens, he was a person of sterling character – kind, loyal, self-deprecating, cheerful in all weather. Everyone who knew him was glad they did.

So….he left a wide circle of friends united in grief, to say nothing of the impact on his widow and children. But I’m speaking – selfishly – of my own loss. This was the only moment of really bad luck I’ve experienced. Is it odd to put it that way? I hope not. That’s the way it felt – like a colossally bad roll of the dice, for there was no one to blame, no one had done anything wrong, it was just a terrible thing. The odds were way against it, it doesn’t happen to most people, but it happened to John, it happened to me – I lost my brother when I was 41.

Over the past 12 years, the grief has abated but the loss never changes. Anyone who’s mourned a loved one knows what I mean – you are diminished by their death. Sizable parts of who I was – larger and more significant than I’d ever realized while he was alive – were simply not available to me anymore. No one else could evoke them. I am a smaller person without John.

I’ve thought about John, and his death, in so many different ways. Dreamed of it, too. I think my dreams have been wiser than my thoughts. Every few months, I dream a version of the same dream. There is John, alive and well. I’m astounded. What happened? I ask. I thought you died. And he never explains, or else there is some sort of explanation but I can’t quite hear it, or comprehend it. It’s as if he tricked us all, somehow. The dream is eerie, but at the same time quite ordinary. Some vast misunderstanding took place, back in 1995, some entirely natural development that I should be able to grasp – John is talking about it like it’s no big deal – and yet I can’t, but I’m so glad he’s alive that the explanation doesn’t matter. These dreams usually end with two feelings: a kind of bemusement at my own denseness, my failure to see what was really going on, all that time I thought he was dead and buried, and a giddy joy to know that I have him back again.

I wrote a poem about this once, and it’s short enough to read. It’s called "Trick":

In dreams a dead friend is sly,

unwilling to say precisely how

or why he fooled you, fooled his daughters, his wife.

But knowledge curls in his smile

(which isn’t quite right, which isn’t the smile

he had before he did the trick)

and suggests a reason, several reasons,

you would approve if you could go

without sleeping. Till then,

trust the reappearance. He and the wet earth

had a misunderstanding. You were weeping,

you blinked and missed — there at the grave-

side — how they embraced and started over.

In dreams your sly friend is alive

but smiling, saying I can explain,

but only and ever smiling.

More recently, as Katie and I were working on songs for our new album, I found myself writing some lyrics I didn’t understand, which often happens. First there was a song about someone Katie christened Felipe, a boy who everyone loves, but who suddenly goes away. And in another song, I wrote about Felipe again. That song is called "The Great Undo," and on a conscious or rational level it’s meant to be about how wonderful it would be if we had an Undo button in our lives, just like that useful icon on our computers. We could press Undo and return to a purer, better version of that draft we’re all working on, with all our stupid edits and changes undone. The song needed a bridge, and I wrote this: "Well, we told you about Felipe/How we thought he’d gone for good/But we’re going to meet that boy again/He was just misunderstood/ He moved into a nicer neighborhood."

And somewhere along here I realized that Felipe was a character who was also my brother John, and that for no rational reason, I was now convinced that he wasn’t gone for good. Again, some huge misunderstanding was involved – the whole idea that death was the end, that loss was permanent. And I suppose the "nicer neighborhood" is Paradise.

So, finally, we’re back to Jesus and the defeat of death. I have had a lucky, lucky life, and yet I am selfish enough to ask God to undo the one piece of bad luck I experienced: I want John to live again, and I want to see him and touch him. In so many traditional understandings of Christian teaching, that’s a promise. Well, I want the promise kept. And I must say again: This is a selfish desire. I don’t picture John reunited with his family, or enjoying the company of God and the angels, though I would be delighted and grateful if this happened – I imagine the two of us together again.

I’m not going to apologize for this selfishness. It seems to me that the Christian message is spoken to our deepest longings, our greatest childlike griefs. True, it contains an invitation to forget ourselves as well, to consider what others may need. Christianity would be unrecognizable without this call to selflessness and compassion. But Christ also speaks to our own hurts and hopes. When the good thief begged Jesus, "Remember me when you come into your kingdom," Jesus did not scorn him for his selfishness. No, he said yes – "You will be with me in Paradise." God does not hold it against me that the pain of John’s loss hurts worse than the pain I feel on behalf of his wife and daughters. God knows my selfish heart; he only asks that I come with my heart open to him.

For all the strong conviction I find in myself that John and I and all of us will meet again in that nicer neighborhood, I still need the explanation. Last Sunday, Bill Milliken described himself as someone without a left brain. My own left brain is very much present, and every time my creative unconscious tells me something is true, the rational mind says, "Oh? And what do you mean by that?"

What do I mean by saying that I believe death is not the end, that the Christian promise of eternal life in Paradise is meaningful, and true, and worthy of confidence? I wish I believed in the soul, some essential Myself-ness that can survive without a body, and get translated to Heaven, a place where everyone is exactly the way they used to be, except . . . no bodies. But I don’t think this is likely. Any picture I have, or can imagine having, of being a self involves having senses, feelings, thoughts, memories – all of which, as science continues to teach us, require incarnation in some sense – and I will come back to that qualifier "in some sense" shortly.

But here is the strange thing. As most of us know, traditional Christianity is equally uncomfortable with this idea of an eternal, bodiless existence. The old, old teaching of the resurrection of the body is meant, I believe, to address this very question. We have the stories of Heaven, but we also have the stories of Jesus’ return, and the physical resurrection of the dead. What little doctrine I know I learned as a Catholic, and the resurrection of the body is part of all the official creeds of the Church.

I don’t literally believe any of this. I think that both the stories about Heaven and the stories about the Second Coming and the bodily resurrection are trying to paint a picture of what eternal life could be like. These pictures are historical, and may not fit your 21st century vision, just as they don’t fit mine.

Here is my modern version – the story I tell myself, that seems to capture how it might be.

We all know what it’s like to imagine someone. We can do it with a real person, by conjuring up an image in our minds of what she sounds like, looks like, feels like. We can do it when we read a book: The sentences come alive and suddenly there’s Sherlock Holmes, with his hawk nose and deerstalker hat, walking the foggy London streets. We can even do it ex nihilo, inventing a character from whole cloth just as Holmes’ creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, did.

This is the most commonplace of experiences. Literally everyone has done it, literally every day. But if we pause to consider it, it is very mysterious, and opens an unexpected doorway onto the question of "real" bodies, and what it means to exist in a world. Let me try to explain what I mean.

Does Sherlock Holmes have a body? Well, on the one hand, no, of course not. Whether in Doyle’s mind or in yours or mine, Holmes is a made-up character. He never existed, was never incarnated in this world. But on the other hand . . . Sherlock Holmes without a body? He’s a man, isn’t he? He lives in London, doesn’t he? If he doesn’t have a body, where does that deerstalker hat sit? Of course he has a body – in his world. Now that world is imaginary, from our perspective – but isn’t our own world imaginary from God’s perspective, if he is truly the creator of the universe? So the question of whether our imagined characters are "incarnate" or not, is not so simple.

I suggest that our own world is one of God’s imagined worlds, a place she has invented and populated. If you ask me, I’m alive and real and I’ve got a body. But if you could enter Sherlock Holmes’ world and ask him, he would say the same thing. The difference (one of many!) between us and God is that we can’t enter Holmes’ world and put the question to him – not even Doyle, Holmes’ creator, could do that – but our Creator is not so limited. He can enter any world he pleases.

I think that when we die, God can, if she wishes, continue to imagine us, in another world. The ancient prayer, "Remember us, O Lord," becomes absolutely literal. It’s our chance to live again. It’s not that some bit of soul-stuff flies out of this world and into the next; rather, God continues to (if you’ll pardon the pun) keep us in mind. Now we are part of a different creation, one that may look more like Heaven, or more like the world at world’s end – I don’t know. But we’ll certainly have bodies – just like Sherlock Holmes!

For what it’s worth, this idea of the afterlife as God’s continued "creation" of us also provides a more merciful solution to the Heaven/Hell dichotomy. For if there’s no soul that has to "go somewhere," then God may choose simply to stop thinking about certain people when they die. For them, death is the end. I would never try to argue for this as some kind of necessary doctrine – it’s just a notion of mine. Personally, I prefer the alternative of Paradise or Nothing, rather than Paradise or Everlasting Gnashing of Teeth.

Anyway, for my dream to come true, I need a body, for me and for John. I need to be able to hug him, and smell him, and shed tears, and shout, "I knew I’d see you again!"

And so I’m waiting. I’m not sure if I’m waiting for the End of Time, or for Heaven, or for the coming of the Christ child – I just know that I’m waiting for the happy ending, the resounding "Yes!" to every question I’ve hardly dared to ask. I’m waiting, selfishly, for a miracle.